Raw ales are nothing new. Tracing back to the Middle Ages in Norway and other parts of Europe, the method is traditionally used to make Sahti, Berliner Weisse, and farmhouse ales, and in its numerous forms is much older than the modern beer styles we know today.

As tends to happen in contemporary craft brewing, raw ale is seeing somewhat of a 21st-century renaissance. The technique is being applied to popular styles like New England IPA and stout, and brewers are releasing packaged brands that utilize the ancient way.

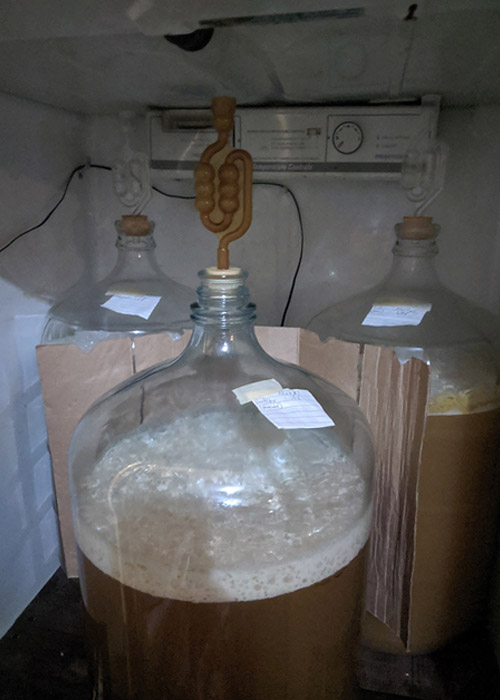

Homebrewers are also trying their hands at this ancient technique. This is everything you need to know to make your first raw ale, including why you should do it, and what to expect when you do.

What Is Raw Ale?

Raw ale is synonymous with “no-boil” beer. Instead of being its own definable style, “raw ale” is akin to calling a beer “dry-hopped” — it refers to the execution of a technique.

In the Middle Ages there was no way to get a batch of beer hot enough to boil, and as far as brewers were concerned, no need to try. This style of brewing would have been the most common method until large metal kettles were made affordable to brewers. There are still farmhouse brewers in Europe brewing this way today: Author Lars Garshol’s blog and book, “Historical Brewing Techniques: The Lost Art of Farmhouse Brewing,” have popularized the interest in these practices and where they occur (especially because there are very few resources in English covering the brewing methods of remote northern Europe). In fact, some historical styles in the Beer Judge Certification Program’s (BJCP) style guidelines are brewed as raw ales, the most common example being Sahti.

The lack of boiling leaves the beer with more protein, creating a fuller mouthfeel and visible haze. Brewers also claim that the malt flavor tends to be more rich and complex in beers that do not undergo a boil step. However, these aspects also cause raw ales to have a shorter shelf life, which is why you won’t many see commercial examples in the U.S.

How to Brew Raw Ale

Pasteurization vs. Sterilization

Because raw ale is not boiled, the wort is never sterilized, but instead is pasteurized. There are two common methods of pasteurization: high-temperature/short-time (HTST) processing, where the temperature is higher (about 161 degrees Fahrenheit) for a short amount of time (15 to 30 seconds); and the slower practice of standard pasteurization, where temperatures are lower and the time is extended, say, 145 degrees F for 15 minutes. Most microorganisms cannot survive temperatures above 140 degrees F. Both pasteurization methods are used during a standard mash (at 145 to 158 degrees F) and mash out (at about 170 degrees F).

Pasteurized wort will be free of microorganisms, but unlike sterilized wort, it may still carry their spores; because of this, homebrewers are typically vigilant about cleaning and sanitation practices when brewing raw ale.

Sarah Flora of the homebrewing YouTube channel Flora Brewing, is always meticulous about cleaning, but says she is even more so when brewing raw ale. “I use Star San [a brewing sanitizer] pretty much constantly. I have a wallpaper sprayer filled with it all the time,” Flora says. “I will spray it on everything — the smallest spill and I’m like, ‘OK, Star San it.’”

Cleaning and sanitizing equipment on both the hot side and the cold side of the brew day will ensure any potential spores have no chance to grow. David Heath, founder of the prolific raw ale brewing channel David Heath Homebrew (also on YouTube), covers extra cleaning steps in each of his videos. For example, brewers typically sterilize their wort chiller by running boiling wort through it at the beginning of chilling. Since there is no boil step in raw ale brewing, a chiller must be pumped with cleaner (like PBW) then sanitizer (like Star San) before the brewing process begins, which he demonstrates in his video about how to brew a raw NEIPA.

Potential Off Flavors

Experienced homebrewers will immediately note the function of the boil to eliminate off flavors is missing from a raw ale brew day. However, the main off flavor that is eliminated in the boil is dimethyl sulfide (DMS), which adds a creamed corn-like aroma to a finished beer. However, instead of depending on the boil to denature and blow off DMS, raw ales keep temperature low enough that DMS never forms.

The precursor to DMS, S-methylmethionine (SMM), doesn’t begin to break down into DMS until wort temperatures reach 176 degrees F. The rate of breakdown isn’t significant until 185 degrees F. By keeping temperatures at or below 185 degrees F, most DMS formation is avoided. The small amount of DMS that is created can be blown off during a vigorous fermentation.

Hop Bitterness and Flavor Extraction

Brewers know that hop alpha acids (compounds found in hops) are issomerized into iso-alpha acids (bitter-tasting compounds we associate with hop flavor) at boiling temperatures. But, alpha acids begin to isomerize at temperatures as low as 175 degrees F, though at a much slower rate (15 percent of that of the boil, according to this journal article from the American Society of Brewing Chemists). In order to extract some bitterness from hops, homebrewers making raw ale may perform a hop stand (holding a consistent temperature in order to isomerize hop acids) for 30 or more minutes at temperatures between 175 and 185 degrees F (ensuring temperatures don’t exceed 185 degrees F to keep DMS at bay).

Flora uses this hop stand method to extract bitterness in her lemon saison.

Heath uses a combination of hop teas and dry hopping to add the desired hop flavor and bitterness to his raw ales. A hop tea is made simply by boiling water, then adding hops, ceasing the boiling, and allowing the hop alpha acids to isomerize and other oils to infuse into the water as the mixture cools. Hops are then filtered out as the liquid is added to finished beer.

Making teas with the desired bitterness takes a bit of experimentation, says Heath. A good rule of thumb is to start small and work your way up: “The first thing you’ll notice is that the same amount as what you would dry hop with is much more potent,” he says.

Protein and Mouthfeel

Another function of the boil is to coagulate protein. This coagulation forms the “hot break,” which contains both haze-forming protein and tannic polyphenols. The hot break is typically left behind in boiled ales.

Without a boil step, raw ales don’t form a hot break, so all of the protein and polyphenols end up in the final beer. This protein creates a fuller mouthfeel, which is ideal in styles that may suffer from thin body. These left-behind compounds can also give the beer more of a “raw malt” or “wort-like” taste because more malt flavor elements make it into the final glass and those elements are not balanced by the typical level of hop bitterness.

Why Brew Raw Ale?

Many homebrewers are interested in making raw ales as an ode to traditional brewing, or out of curiosity for historical or foreign styles. For Heath, these come into play, but with another, less common reason for delving into ancient brewing styles: efficiency.

“Not only is this a piece of history and a fun process but it is also a time saver,” says Heath. Time is saved because the 60- to 90-minute boil is eliminated, as is the time it takes to heat wort from roughly 170 degrees F mash-out temperature to boiling. Beyond time, the energy used to heat the water and to maintain the boil is also saved.

“I know of people doing it because with the electric systems that are out now, getting a rolling, rolling boil is sometimes difficult,” says Flora.

Which Styles Work Well When Brewed as Raw Ale?

As previously mentioned, raw ales will naturally have a fuller, creamier mouthfeel than beers with the same recipe that have a boil step. This lends the raw ale technique to work well for modern styles that benefit from a chewy texture, like NEIPA and stouts.

Many brewers, including Heath, have experimented with NEIPA as a raw ale because the style doesn’t require much bitterness from hops, and benefits from the full flavors of the malt and creamy mouthfeel created by protein that raw ales provide.

Flora used the raw ale technique on her Berliner Weisse, a style that is known for having a watery consistency. “It had a little thicker body than traditional Berliner Weisses I’ve had that have been boiled,” she says. The high amount of protein and low amount of isomerized hops (which act as an antibacterial agent) cause this beer to be unstable, though it will last a few months when stored properly at home. “I just poured a sample,” said Flora of her Berliner Weisse that had been brewed just over two months earlier. “It’s held up really well, tastes like a really nice lemonade.”

But this fuller Berliner Weisse can only really be enjoyed by those who brew it themselves, or those lucky enough to have an ambitious homebrewing friend.

“The only real issue is shelf life,” Heath says. “This keeps it away from the commercial brewery market, so as such to try raw ale it will need to be homebrewed.”