The Gladstone Arms in London’s Southwark borough might seem like the most traditional of British pubs, named after a four-term U.K. prime minister from the 19th century and boasting of a mention in a Charles Dickens novel. But in the place of established British staples like steak and kidney pie, bangers and mash, and Yorkshire pudding, the menu lists dishes like Kid Goat Keema Pie and Chicken Tikka Masala pie. On weekends, guests can order a Sunday roast, a U.K. classic, but that offers even more curveballs, pub director Megha Khanna explains.

“Obviously the Sunday roast is a very British thing, but we’ve integrated it with Indian flavors, so it’s like a curry roast,” she says. “Curry is obviously quite popular in Britain. And if you marry that up with beer, which people love, it’s just a match made in heaven.”

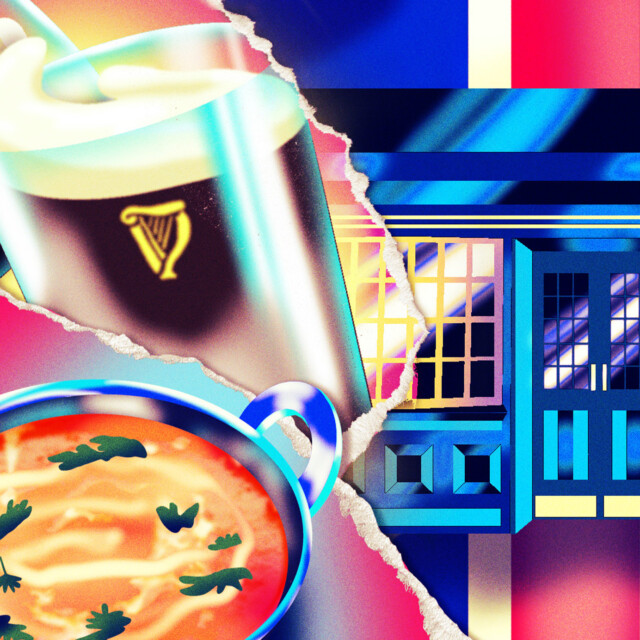

Tourists expecting a fictional vision of the classic British pub — be it one from Charles Dickens or Ted Lasso — might be surprised by a Sunday roast that features British ales paired with smoked Delhi butter chicken, Bombay potatoes, and Paneer Makhani pot pie. But pubs celebrating a strong desi (or South Asian) influence are a big trend across the U.K., with a new guidebook, “Desi Pubs,” appearing last May.

And it’s not just South Asia that has put its mark on the traditional British pub. While often thought of as a purely British — and often even just “English” — cultural monolith, the British pub includes an array of diverse cultural influences from outside Britain. In recent years, authors and journalists have worked to uncover the international elements behind the U.K. pub, highlighting the rich diversity that has helped to create it.

Noodles, Curry, and Rhinos

Outsiders aren’t alone in misunderstanding the British pub, according to Des de Moor, author of the beloved guidebook “London’s Best Beer, Pubs and Bars.” For years, Britons have also looked at the pub through idealistic — and often nationalistic — lenses.

“I think there’s a kind of romanticization of the idea of the pub, which treats it as this sort of unchanging institution that relates back to Merry England,” he says. “Jolly images of medieval times and so on, which is, of course, all utter nonsense.”

Instead of being a purely British invention from the halcyon days of “Merry England,” numerous foreign influences have helped to create British pub culture. In recent years, some of the most visible might have their origins in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. But a generation or two ago, they predominantly came from the Republic of Ireland — geographically part of the British Isles, but decidedly not part of the United Kingdom.

Originally from Ireland, Oisín Rogers has been working in London pubs since 1989, most recently running the celebrated Guinea Grill in Mayfair. An oversize Irish population among pub management and employees in the 1990s, he says, greatly influenced U.K. pubs, putting an Irish touch on everything from food to atmosphere.

“In the ‘90s, the force was very strong to move towards Irishisms in terms of service, lots of Guinness, live music in the pub, craic from the chaos,” he says. “It’s stereotypical of me to say that we drink more, we have more fun, and we add more color to pubs, but the fact is, that’s completely true. When I was in big pub companies that had hundreds of pubs, 35 to 50 percent of the managers were Irish.”

From that high point a couple of decades ago, he estimates that the number of Irish pub managers in London has now dropped to below 10 percent. In their place, Brazilians, Eastern Europeans, Australians, New Zealanders, and other immigrants are now managing, staffing, and owning pubs. Around London, various immigrant communities are all putting their own spin on things.

“If you go to a pub in Stockwell, for example, where there’s a large West Indian community, and there’s live music on, the chances are that you’re going to get something that the locals want to go and see,” he says. “You will find somebody singing some incredible blues and West Indian music, and you might find some steel drums and guys having a really great time drinking bottles of Guinness. And that can be reflected for any of the beautiful ethnic villages in London where people live.”

Both Rogers and de Moor cite the rise of the food-focused pub, or gastropub, as one of the big shifts in British pub culture. (Though the trend started earlier, the term “gastropub” itself dates to 1991.) That era’s interest in “restaurant-quality” pub food, Rogers says, often ended up bringing in more influences from outside Britain. That led to places like north London’s Faltering Fullback, which describes itself as “a charming, well-loved Irish pub” which serves “not quite Irish grub,” by which it means Massaman curry, pad see ew, green curry, and other classic recipes from Thailand.

“If you run a pub, it’s very easy to go out and find somebody who might be an immigrant or somebody from another country and say, ‘Hey, why don’t you take over my kitchen and do something cool?’ he says. “A lot of places that do Thai food, that’s the situation. And you can be guaranteed a hundred percent that if you look in that kitchen, there are Thai people in there cooking the same food as they would in Bangkok.”

At the Gladstone Arms, such influences go way beyond the food.

“We also do Indian events, Diwali parties and that kind of stuff,” Khanna says. “It’s just a big cultural burst.”

Naturally, guests can also find international elements in the glass.

“Alongside the food, we have an influence on the drinks,” she says. “We’re currently serving White Rhino Lager, which is from Gwalior in India, and we’ve got Indian whiskies.”

Changes at Home and Abroad

While many North Americans might be surprised by the diversity that can be found in British pubs today, they shouldn’t be disappointed by the change. De Moor says that the idea of the British pub as a kind of community center, where everyone can gather and socialize together happily, is not necessarily reflective of the way all British pubs functioned in the past.

“I think there’s a rose-tinted view of this, because pubs, of course they’ve been part of communities, but they’ve also been reflective of the divisions in communities,” he says. “That was very much the case when I was growing up. There were pubs I felt I couldn’t go into because they were very aggressive, male-dominated places. And if you weren’t the kind of person who fitted into that, you’d feel very, very, very vulnerable in them.”

In the past, many underrepresented and marginalized groups would have felt that sense of vulnerability in pubs — if they were allowed in at all. In the 1950s and ’60s, activists, actors, and athletes like the boxer Len Johnson campaigned to end the “colour bar” that banned black and Asian guests from many pubs across Britain.

The diversity in modern British pubs seems indicative of a much more diverse society, especially in the capital: Today, London is one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the world, where over 300 languages are spoken, and where more than a third of the population is foreign-born. Small towns and rural regions might enjoy less diversity, but they are still affected by international currents. As the magazine Country Life has pointed out, South Asian curry is arguably Britain’s national food at this point.

Interestingly, British-style pubs outside the U.K. don’t often reflect the changes that have taken place inside the country. British-style pubs the Manchester Arms in Atlanta, Ga., and the Brewers Arms in Dallas both offer bangers and mash, fish and chips, shepherd’s pie, and other traditional meals, but no form of curry is listed on either menu.

For non-Britons, catching up with the changes probably requires a trip to the U.K. If you go, remember that what you see might be temporary. The U.K. hospitality trade has been upending itself in various ways every few years for decades, Rogers says, adding he believes that Brexit is unlikely to change that tendency. De Moor points to the growth of the “micropub” as another way that British pubs have innovated in recent years: creating a new genre of small, independently owned drinking establishment that focuses on cask ales and conversation, which also “shuns all forms of electronic entertainment and dabbles in traditional pub snacks,” according to the Micropub Association. The first micropub, the Butchers Arms in Herne, Kent, only started up in 2005, followed by a wave of others, including the award-winning Dodo Micropub, which opened in West London in 2017. Other changes and innovations are likely to follow.

“You know, pubs are not fixed, non-changing things — they always reflect society,” de Moor says. “The nice thing is, if you come to somewhere like London and you get good advice and you know where to go, you can find a really wide range of pubs. See some of the remaining heritage pubs from the late 19th, early 20th century — they’re absolutely spectacular and unmissable. But I’d also say to look at micropubs, look at desi pubs, look at that whole range of the pub repertoire.”

You might even find some familiar features.

“Increasingly, there’s a U.S. influence, too, that has come through craft beer,” he says. U.K. brewery taprooms might look especially familiar to visitors from North America. “The brewers and the people who have set these up have often been to the U.S. and seen what’s going on there, and tried to copy that style over here.”