The next time you order a Manhattan or another rye whiskey cocktail, don’t be afraid to ask for a bottle beyond Rittenhouse, Whistle Pig, Pikesville, High West, or Old Overholt. You could, for example, ask to have your drink made with one of the many new rye whiskeys coming out of India, Germany, or Finland.

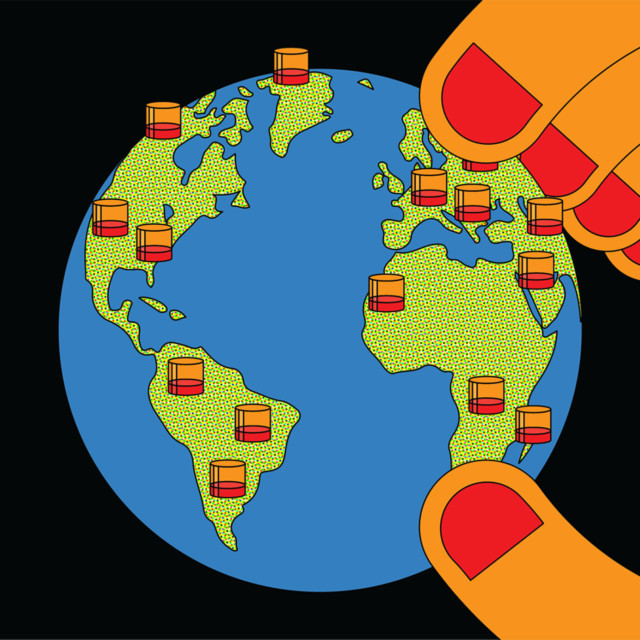

Once considered a purely North American spirit, rye whiskey has gone global in recent years, with new producers popping up around the world. Far from rye whiskey’s ancestral homelands in Pennsylvania, Maryland, New York, and Canada, international distillers have begun creating their own takes on the spirit, pushing the boundaries of what was once a specifically New World style and possibly changing the global paradigm for what good whiskey should taste like. At The Gospel, a rye whiskey maker in Melbourne, Australia, co-founder Andrew Fitzgerald says that the growing interest in rye is partly fueled by cocktail culture, as drinkers start to move on from bourbon or Scotch.

“What we’re finding is that rye is the ‘other’ whiskey that somebody will try,” he says. “If you’re a single malt drinker and you’re thinking about bourbons, you’ll probably try rye first, and bourbon drinkers are trying rye because it’s being promoted at the bar. It’s appearing in more cocktail lists, and bartenders are translating to people what rye whiskey should taste like. People are catching on.”

A New School

Like many producers, The Gospel is relatively new, only selling whiskeys since 2019. Several other international ryes are of similarly recent vintage. Finland’s Kyrö Malt Rye Whisky officially launched in 2020, the same year that Germany’s Slyrs distillery came out with its Bavarian Rye, while India’s Amrut Rye appeared in 2016.

But it’s not just about the newcomers. Even more established producers like Denmark’s Stauning — which started making its rye whiskies in 2006 — are also enjoying the new wave of interest in the spirit.

Although rye whiskey might be thought of as coming only from North America, the grain has a distinctly local connection in Denmark, explains Stauning co-founder Hans Martin Hansgaard.

“We started making rye whisky a long time ago,” he says. “Denmark, as part of our cultural history, has a very close relation to the crop rye. The national food of Denmark is rye bread. We eat a lot of it. We felt that it made a lot of sense to explore rye whiskies in Denmark and make the best possible version of a rye whisky we could come up with.”

Other makers have expressed similar local connections. Austria’s Waldviertler Whisky is located in the village of Roggenreith, a name that translates as a forest clearing where rye (roggen in German) is grown. Distiller Jasmin Haider-Stadler says that Waldviertler’s use of rye has a direct connection to that etymology. “Here, the grain finds optimal conditions for growing,” she says. “That was also the reason why we specialized in rye and rye malt whisky. We wanted to use the raw materials that are right on our doorstep.”

Those local associations — and local ingredients — influence the taste of many non-North American rye whiskeys as well. Rye is famous for its peppery, spicy notes, as well as a touch of nuttiness. But at The Gospel, Fitzgerald says, experiments have shown that the flavors and aromas of the distilled spirit can vary widely based on the specific cultivar of the grain, as well as where that grain is grown.

“We’ve taken the same variety of rye sourced from two different locations, one being a very wet region called Gippsland in Victoria, and one being a very dry, arid region where we get most of our grain from,” he says. After distilling them separately, he says, the two spirits tasted very different from each other. A second experiment with two different varieties of rye that were both grown in the same region yielded similarly divergent flavor profiles. “That’s actually driving a lot of what our trial is — trying to experiment with rye as a grain,” Fitzgerald says.

Beyond the Grain

While the rye grain has its own character, other aspects of whiskey making can add an array of nuance to the finished spirit, like the use of malted rye instead of — or along with — unmalted rye, the traditional form of the grain used in American whiskeys. In terms of the grist, other variations can include using all rye, like The Gospel and Amrut, or with the addition of barley malt, wheat, corn, or other grains, as at Stauning and Slyrs.

At Stauning, Hansgaard says, the rye whisky follows all of the requirements for an American rye, including the use of at least 51 percent rye and a minimum age of at least two years, but the locally sourced rye grain is malted using the distillery’s traditional floor maltings.

“I would say that is the most important difference to American rye,” he says. “Rye whisky can be maybe the most difficult whisky for non-whisky drinkers to approach because it’s so spicy. It can be almost fiery and very spicy to drink. But when we malt it, we develop the sweeter side and the fruitier side in our rye whisky.”

At Waldviertler Whisky, both malted and unmalted local rye grains are used, in both light and dark roasted forms. But for even more character, the spirit is aged in Austrian oak barrels.

“We start with virgin oak and store the whisky in it for about three and a half years,” Haider-Stadler says. “Austrian oak has a lot of natural tannins, which gives a particularly intense wood flavor to the whisky.”

Other distillers, including The Gospel in Australia and Slyrs in Germany, use new American oak to age their whiskeys. For The Gospel, that helps to create a spirit that has both Australian and U.S. character, Fitzgerald says.

“Because of the dry and distressed grain that we source, it’s very cereal-forward whiskey,” he says. “So what we’ve tried to do is actually marry that expression, which almost tastes dusty in an Australian sense, and try and blend in the American influence of the sweeter barrel, oak, and all that.”

Despite those and other nods to the spirit’s origin in North America, there’s a chance that specific regional styles of rye whiskey could develop. At Slyrs, master distiller Hans Kemenater says that one aspect of a European rye style might be its approachability.

“In my opinion or how I taste it, the European ryes are not as strong as the American ryes,” he says. “American ryes are often bottled at 48 percent or another high proof level. [In] European styles, the alcohol level is around about 40, 41, or 42 percent. The European style is more drinkable in a pure way.”

The Spirit Comes Home

Many of these new versions are starting to show up in the place where rye whiskey was born. After 15 years, Stauning sent its first shipment of Danish rye whisky to the U.S. in 2021, with The Gospel becoming available through online vendors in the U.S. at the end of the same year. That makes sense, given the size of the U.S. market, its historical connection to rye whiskey, and the popularity of rye whiskey in North America’s contemporary cocktail scene.

As such, Fitzgerald thinks that U.S. and Canadian drinkers should get ready to try something new. “I’m excited by the people who are doing different things with rye,” he says. “Where to look for the next great rye whiskey? Outside of America.”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!