As it turns out, swindling vintage absinthe collectors out of $50,000 or so isn’t all that difficult. Fans of the OG version of the legendary spirit are thirsty, so to speak, and it’s fairly easy to find buyers for a highly sought-after bottle. In particular, collectors want the versions that were made before 1914, when the gradual, country-by-country bans on absinthe mostly ended its legitimate production for about a century. Running a con might require a bit of ingenuity, but it can be done. The hard part, of course, is not getting caught.

For many years, the man I’ll call Stephen got away with it, selling scores of forged historic bottles for $3,000 or more, playing some of the world’s biggest absinthe collectors for dupes.

Until they figured it out.

“He had been involved in absinthe for so long, he was so well-respected,” says Cary René Bonnecaze, a collector and antiques and replicas dealer who bought several pre-ban bottles of absinthe from Stephen that were later revealed to be fakes. “Everyone bought from him. Everyone knew him.”

A Hidden World

To understand the world of modern absintheurs is to enter a true demimonde: a small, tight-knit community, spread around the world, which connects mostly online. In real life they meet up only sporadically, usually at festivals like the Absinthiades, an annual celebration held in Pontarlier, France, the home of several of the spirit’s original producers. Many collectors have known each other for decades. Sometimes they ship samples to each other, especially if one of the group finds a vintage bottle that can be split up.

A London resident with a posh, double-barreled last name, Stephen was a member of that world and a regular at the Absinthiades. He was also a member of several private, absinthe-focused Facebook groups and online forums where fans of the drink and its rich history would share pictures of vintage paraphernalia — antique absinthe spoons, water fountains used to dilute the drink and make it “louche,” or empty bottles dating from before the ban, as well as their rare discoveries of authentic vintage spirits — and stay in touch.

Ultimately, being spread out and familiar with sharing information online helped Stephen’s victims figure out what was going on and ultimately prove that his pre-ban absinthes were fakes. But Stephen also used this situation to his advantage, playing different collectors against each other and sending messages to offer discounts for his “friends,” Bonnecaze says.

“Being friends, you know, he was always giving me the ‘kinfolk’ deal,” he says. “And that was also part of the allure. He would also tend to mention that ‘so-and-so is really interested in it and wants it,’ but he’d give me until Wednesday, and if I can do something before Wednesday, then he’ll go ahead and hang on to it. But it was just all a con game.”

A Bottle Job

How do you trick some of the world’s most knowledgeable vintage absinthe lovers with a counterfeit? To start, you need a bottle — or several.

Luckily for Stephen, empty historic absinthe bottles are not uncommon on auction sites in France. Sometimes they’re missing a label, and of course they’re always missing the absinthe. But vintage labels are also relatively easy to source on their own.

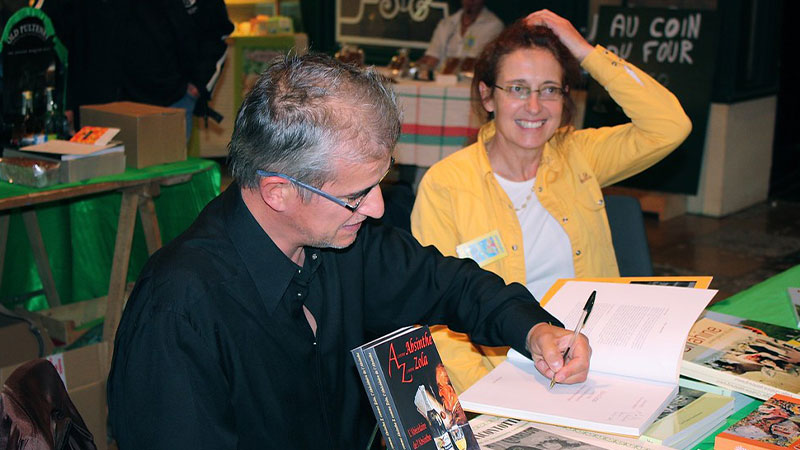

Patrick Roussel is one of the world’s authorities on absinthe antiques. Depicting a cartoon version of what might be a 19th-century version of himself, his business card says that he is a collector of every kind of absinthe paraphernalia, that he buys at good prices, and that he is willing to travel throughout France. He remembers Stephen asking for advice about collectibles.

“He was a fun, likable person,” Roussel says. “We met several times over the course of about 10 years. I also regularly sold him antiques, mostly glasses, and towards the end also some labels.”

If you buy an empty absinthe bottle from French eBay for $50 or so, plus a label from a collector, you’ll need to fill the vessel with something. By all accounts, Stephen had a good nose and a good sense of what a vintage absinthe should taste like, having sampled several authentic vintage absinthes tracked down by his friends. He purchased a few high-quality, modern absinthes and either filled the bottles with single absinthes or a mix. For a vintage note, he added a bit of Tarragona, a collectible but not super-rare version of absinthe made by Pernod in Catalonia, where it was not formally banned, until the 1960s.

Recreating the right flavors inside the bottles was just a backup plan for Stephen — most folks believe he was hoping it wouldn’t come to that.

“He was counting on the fact that very few people wanted to open such rare bottles,” says Martin Žufánek, a distiller of cult modern absinthes whose products were thought to have been used in the forgeries, along with those of other contemporary distillers.

As the owner of a substantial pre-ban collection, Bonnecaze says that he has rarely opened any of the full, vintage bottles he owns, including the forgeries he purchased from Stephen.

“I think of it as like a living thing,” he says. “And once you open it, you kill it.”

But if you sell enough supposedly vintage bottles, eventually someone will want to try one.

Suspicions Arise

Many in the absinthe world credit what happened next to Scott MacDonald, author of the book “Absinthe Antiques.” A friend he won’t name shared a supposed vintage bottle with him, but MacDonald immediately knew what it was.

“I noticed right away that there was a very recognizable base from a modern French distillery in there,” he says. “I did a side-by-side comparison with a bottle made by this distillery. The color, the aroma, the taste, the finish, everything: exact. With a tiny little difference.”

Without naming names, MacDonald shared his suspicions of forged vintage absinthe in a private Facebook group, where he received some pushback on his claims. But at the same time, Roussel had been following some clues on his own, initially becoming suspicious after seeing the sheer variety of vintage absinthes Stephen was claiming to have located.

“I was struck by the number of different bottles he found,” Roussel says. “I am also able to purchase old bottles, but never so many different brands.” After his suspicions were raised, he began keeping track of Stephen’s claims. “I started to make a photo library of the bottles he shared on forums.”

At the time, Stephen’s boasts did come off as a bit “extra.” While researching a possible article about absinthe collectors, I exchanged several DMs with Stephen, since we had met in person at the Absinthiades and were both members of some of the same online groups. He replied that he would rather not be interviewed. “I have over 100 bottles of pre-ban, and because of that, prefer the privacy,” he wrote. At the time, a young-ish man of apparently average means with a collection worth $300,000 or more was hard for me to wrap my head around.

Things were more obvious for the real absintheurs. Roussel was following all of the internet sales of empty bottles in France and saving the photos. “Soon, an empty bottle without a label that was sold online in France showed up full, with a label,” he says. Stephen was offering it for sale. And then, visiting the Swiss distiller Patrick Grand, Roussel saw two full, supposedly antique bottles that Stephen had traded to Grand in exchange for some bottles of his modern absinthe.

“Looking at the bottles, I knew that they were fake,” he says. “One of the bottles wasn’t the right one for the brand. The labels were placed too high. The wax seals were just bad copies of the bottle stamps. And the two absinthes had the exact same color.”

In April 2019, Roussel and the others went public. They had proof in the form of photographs, whereby an empty historic bottle with a distinct crack in the glass or a uniquely torn label that was sold on French eBay later showed up in the form of the full bottles being sold by Stephen, with the same distinct crack and torn label. Another member of the group with access to a professional lab had performed chemical analysis of some of his absinthes, which proved that they were way too young to be vintage.

At first, Stephen denied the allegations.

“I wrote to him a few times privately and, as expected, he eventually told me that it was only one time that he did it,” Bonnecaze says. “I sent more photos to show him, ‘No, you’re still lying.’”

Assessing the Damage

In the aftermath, Stephen blocked all of his absinthe friends on Facebook. He hadn’t blocked me when I started researching what happened, however, and I got confirmation that he received my messages asking him for his side of the story. But when I followed up the next day, I got the same message as everyone else: “You can’t message Stephen.”

The forgery ended up hurting absinthe culture in a number of ways. One dealer of legit historic absinthes told me that Stephen damaged the vintage absinthe business very badly, costing him several clients. Scott MacDonald says that the fake vintage absinthes clouded the concept of what historic absinthe actually tasted like. It’s not impossible to imagine, he points out, that some modern distillers are trying to make historic-inspired absinthes that are actually styled after a single contemporary spirit or a mélange of modern absinthes with some Tarragona thrown in.

It’s unclear how many people Stephen the absinthe forger ripped off, or even how much money he made from his counterfeits. Roussel estimates his take as around 40,000 euros, or about $46,000 at today’s rates, while MacDonald says he thinks the amount might be over $100,000. What’s more clear is how much the absinthe forger hurt his friends: people who had shared drinks with him, eaten meals with him, and traveled to festivals with him.

“I was pretty devastated that they were worthless,” Bonnecaze says, when asked about the fake bottles he had purchased. “And when I say worthless, again, not so much monetarily. But for me, it’s a thrill: I love the history, wondering where that bottle could have been, where that spoon could have been. So for me, it was really disappointing. And then I guess it all kicked in where I started to realize, you know, that my friend has been lying to me.”

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!