Newspapers and magazines featured arresting images from France’s most famous wine regions earlier this month, showing romantic French vineyards filled with burning candles and oil lamps in an effort to protect the young grape buds from the effects of a sudden cold snap. Follow-up stories have often focused on how much of France’s grape harvest will be lost to the freeze, and which great French wines might be affected.

But the extreme cold that threatened France’s wine regions at the start of April is less than half the story. In fact, the recent cold snap extended across the European continent, affecting growers a thousand miles or more from Bordeaux and Burgundy. Moreover, drinks businesses beyond wine are being impacted.

In Umbria, central Italy, waves of freezing nights in early April chilled the Montefalco wine region to the bone. Filippo Antonelli, president of the local wine cooperative Consorzio Tutela Vini Montefalco, told VinePair that the region’s beloved Montefalco Sagrantino DOCG is unlikely to be affected this year, since Sagrantino is a late-ripening grape.

The bad news? The region’s other favorite varieties suffered. The damage is estimated to be between at least 10 and as high as 70 percent, threatening this year’s Montefalco Rosso DOC and Montefalco Grechetto DOC vintages.

“The varieties such as Sagrantino and Trebbiano, being later, were less affected than Sangiovese and Grechetto, which are the most affected grapes [here],” Antonelli says. “Consumers can therefore expect price increases, as the harvests will be lower, especially as regards [to] white wines, which often come out in the same year as well.”

Other wine regions up and down the Italian peninsula were hit by a heavy frost. In Piedmont, the unseasonal cold damaged up to 40 percent of early ripening grape varieties, the Quotidiano Piemontese newspaper reported, with particular damage in the Nebbiolo-growing areas of northern Piedmont and Barbera vineyards near Asti, Nizza Monferrato, and in the Tiglione Valley. Claudio Biondi, president of the Lambrusco Protection Consortium, told the ANSA news agency that up to 80 percent of the Lambrusco harvest in some areas of Emilia-Romagna might be damaged.

Daniele Toniolo, a sommelier who designs and leads tours to Italian wine regions for Europe Sideways, says that the cold wave is a particularly hard bounce for the country’s smallest producers, since their businesses were already suffering because of the pandemic.

“Covid-19 restrictions severely affected their economics, since most of them also offer accommodations and cooking classes, truffle-hunting trips and other outdoor activities,” Toniolo says. “They’ll recover, but it is a tough break, especially at this point. They’re really looking forward to welcoming visitors back again.”

Other parts of Europe had similar experiences: Grape growers in Belgium, Switzerland, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and elsewhere were forced to take measures to protect their plants during the recent freeze. Although the vineyards filled with candles were extremely photogenic, farmers actually used a number of different techniques to protect their crops, including smoke, steam, and even ice, spraying water that, when frozen, protected the delicate buds from even lower air temperatures further below freezing.

In Piedmont, the Franco Conterno winery lost about 60 percent of its grape crop, mostly the early ripening Nebbiolo, according to co-owner and winemaker Daniele Conterno. The winery managed to save many of its youngest, recently planted vines, he says, by burying them underground.

In Charente, France, vineyards were protected by tall towers that draw warmer air from higher up down to the plants on the ground. Only about 10 percent of the Charente vineyards were ultimately affected by frost on the nights of April 7 and 8. However, those grapes are primarily destined to be made into Cognac, not wine.

For the producers in Montefalco, candles, towers, and other heating equipment couldn’t really be used to stave off the frost, Antonelli says, due to the terrain and the scale of the vineyards. Instead, local growers tried to protect the young grape buds through their choice of pruning dates.

“In our area it was not possible to resort to particular deterrents [like candles],” Antonelli says. “The only deterrent was the choice of the timing of pruning. Those vineyards that were pruned earlier suffered more from the frost than those that were pruned late.”

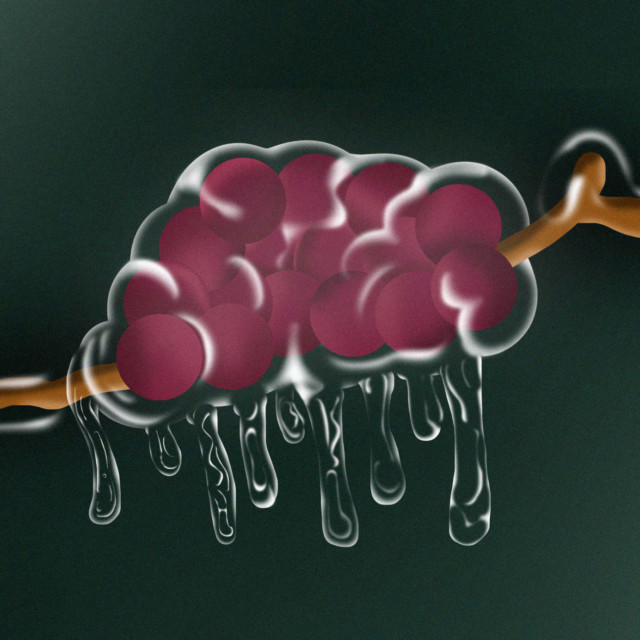

The frost damage extended far beyond grapes. Half of the stone fruit grown in Piedmont might be gone this year; other areas saw even greater losses. The Mikulov wine region in South Moravia, Czech Republic, has been famous for its wines for centuries, possibly even millennia, and was once said to be the source of most of the wine consumed in nearby Vienna. Among fans of so-called “wild” beers, however, the region is also known as the home of Wild Creatures, a Belgian-style brewery focusing on spontaneous fermentation, often using local fruit. Owner and brewer Jitka Ilčíková says that the recent cold snap was particularly hard on South Moravian apricots, which she normally uses in a Wild Creatures beer called Fly With Me.

“This fruit is very sensitive, and when the weather is cold during the blossoming there is no chance for the harvest that year,” she says. “We’ll know more within a week or two. Much of the harvest is gone for sure. But not all of the trees are in blossom at the same time, so hope is still alive.”

While this year’s frost made headlines, growers acknowledge that it really isn’t so uncommon of an occurrence. In 2020, for example, Ilčíková lost her entire apricot crop.

“Last year was much more catastrophic,” she says. “The pity is that the situation is very similar just one year later.”

Other makers have taken a lesson from the late frosts of recent years. Pruning times were changed for the grapes at Antidoot, a cult producer of farmhouse beer, cider, and wine in Kortenaken, Belgium. Owner and brewer Tom Jacobs says he attempted to delay this year’s bud opening, or “budbreak,” after losing fruit due to an unseasonably late frost last year. “This year, we did the pruning of the [grape] vines very late, around half-March. This way the budbreak comes later,” he says.

Though Antidoot seems to have saved its grapes, some of its other fruit was lost — including the apricots and peaches that Jacobs had hoped to use in upcoming Antidoot beers.

While most regions in Europe seem to be through the worst of the late freeze, the story isn’t over yet: Meteorologists have been predicting another set of cold nights in many areas through the end of April, with the possibility of more frost returning later in the spring. The surprise freeze that damaged his grape crop in 2020, Jacobs notes, actually happened in mid-May.

That could mean another set of arresting images to come — and plenty of continuing uncertainty for drinks producers, distributors, retailers, and consumers. After a year like 2020, most of us realize that nothing is ever guaranteed. But higher prices and limited availability both sound like safe bets in 2021.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!